Researchers at North Carolina State University have devised a machine learning (ML) method to improve large-scale climate model projections and demonstrated that the tool makes models more accurate at both the global and regional level.

These findings were facilitated by the National Science Foundation, under grants 2151651 and 2152887 and published in the paper, ‘A Complete Density Correction using Normalizing Flows (CDC-NF) for CMIP6 GCMs’, in the journal Scientific Data – Nature. The paper was co-authored by Emily Hector, an assistant professor of statistics at NC State; Brian Reich, the Gertrude M Cox distinguished professor of statistics at NC State; and Reetam Majumder, an assistant professor of statistics at the University of Arkansas.

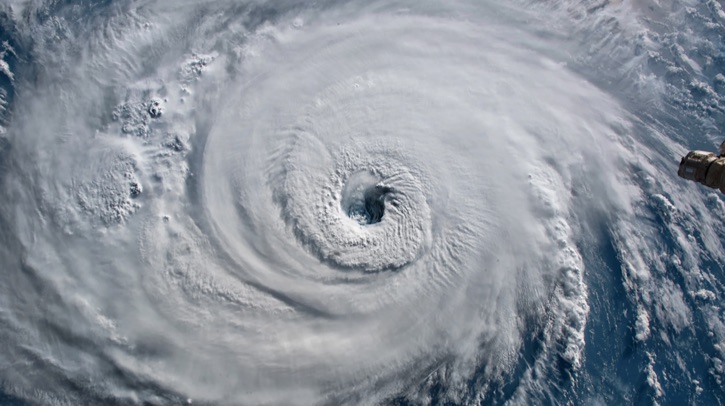

Planning for extreme weather

This solution is expected to provide policymakers with improved climate projections that can be used to inform policy and planning decisions.

Shiqi Fang, first author of a paper on the work and a research associate at North Carolina State University, said, “Global climate models are essential for policy planning, but these models often struggle with ‘compound extreme events,’ which is when extreme events happen in short succession – such as when extreme rainfall is followed immediately by a period of extreme heat.

“Specifically, these models struggle to accurately capture observed patterns regarding compound events in the data used to train the models,” Fang added. “This leads to two additional problems: difficulty in providing accurate projections of compound events on a global scale; and difficulty in providing accurate projections of compound events on a local scale. The work we’ve done here addresses all three of those challenges.”

“All models are imperfect,” commented Sankar Arumugam, corresponding author of the paper and a professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at NC State. “Sometimes a model may underestimate rainfall, and/or overestimate temperature, or whatever. Model developers have a suite of tools that they can use to correct these so-called biases, improving a model’s accuracy.

“However, the existing suite of tools has a key limitation: they are very good at correcting a flaw in a single parameter (like rainfall), but not very good at correcting flaws in multiple parameters (like rainfall and temperature),” Arumugam continued. “This is important, because compound events can pose serious threats and – by definition – involve societal impacts from two physical variables, temperature and humidity. This is where our new method comes in.”

Validating the method

The new method makes use of ML techniques to modify a climate model’s outputs in a way that moves the model’s projections closer to the patterns that can be observed in real-world data.

The researchers tested the new method – called Complete Density Correction using Normalizing Flows (CDC-NF) – with the five most widely used global climate models. The testing was done at both the global scale and at the national scale for the continental United States.

“The accuracy of all five models improved when used in conjunction with the CDC-NF method,” said Fang. “And these improvements were especially pronounced with regard to accuracy regarding both isolated extreme events and compound extreme events.”

“We have made the code and data we used publicly available, so that other researchers can use our method in conjunction with their modeling efforts – or further revise the method to meet their needs,” concluded Arumugam. “We’re optimistic that this can improve the accuracy of projections used to inform climate adaptation strategies.”

In related news, Dr Kianoosh Yousefi, assistant professor of mechanical engineering in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Texas at Dallas, recently received an Office of Naval Research 2025 Young Investigator Program (YIP) award of US$742,345 over three years to improve hurricane forecasting with machine learning (ML)