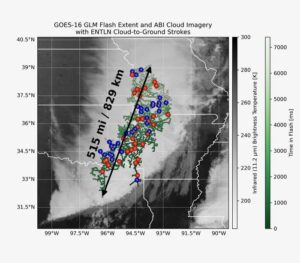

Researchers at Arizona State University have used satellite-borne lightning detectors to measure a record-setting lightning megaflash that streaked across the Great Plains for 515 miles during a major thunderstorm in October 2017. Its horizontal reach surpassed the previous record-holder by 38 miles yet went unnoticed until this re-examination of satellite observations of the storm.

Leveraging geostationary satellites

Satellite-borne lightning detectors in orbit since 2017 have made it possible to continuously detect lightning and measure it accurately at continental-scale distances. Parked in geostationary orbit, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s GOES-16 satellite detects around one million lightning flashes per day. It is the first of four NOAA satellites equipped with geostationary lightning mappers, joined by similar satellites launched by Europe and China.

“Our weather satellites carry very exacting lightning detection equipment that we can use to document to the millisecond when a lightning flash starts and how far it travels,” said Randy Cerveny, an Arizona State University president’s professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning.

“Adding continuous measurements from geostationary orbit was a major advance,” said Michael Peterson at the Georgia Tech Research Institute. “We are now at a point where most of the global megaflash hotspots are covered by a geostationary satellite, and data processing techniques have improved to properly represent flashes in the vast quantity of observational data at all scales.” Peterson is first author of a report in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society documenting the new lightning record.

Studying lightning megaflashes

According to satellite observations analyzed by Peterson, less than 1% of thunderstorms produce megaflash lightning (a lightning bolt that reaches beyond 100km). They arise from storms that are long-lived, typically brewing for 14 hours or more, and massive in size, covering an area comparable in square miles to the state of New Jersey. The average megaflash shoots off five to seven ground-striking branches from its horizontal path across the sky.

“We call it megaflash lightning and we’re just now figuring out the mechanics of how and why it occurs,” said Cerveny, who serves as rapporteur of weather and climate extremes for the World Meteorological Organization, the weather agency of the United Nations. “It is likely that even greater extremes still exist, and that we will be able to observe them as additional high-quality lightning measurements accumulate over time.”

While megaflashes that extend hundreds of miles are rare, it’s not at all unusual for lightning to strike 10 or 15 miles from its storm-cloud origin, Cerveny said. And that adds to the danger. Cerveny highlighted that people don’t realize how far lightning can reach from its parent thunderstorm.

“That’s why you should wait at least a half an hour after a thunderstorm passes before you go out and resume normal activities,” Cerveny said. “The storm that produces a lightning strike doesn’t have to be over the top of you.”

In related news, a world-first multi-sensor detection of an intense gamma-ray flash was recently observed by researchers from the University of Osaka, when two lightning leaders collided. Observations across a wide radiation spectrum enabled precise measurement of the electric current produced during this extreme event and demonstrated that the gamma-ray flash preceded the collision of the lightning leaders between the thundercloud and the ground. Read the full story here