CIRES and CU Boulder have become the first to detect a tsunami caused by a landslide using data from a ship’s satellite receiver. The research, which is published in Geophysical Research Letters, demonstrates that shipborne navigation systems have potential to improve tsunami detection and warning, the institutions say.

Recording the tsunami

On May 8, 2022, a landslide near the port city of Seward, Alaska, sent debris tumbling into Resurrection Bay, creating a series of small tsunami waves. The R/V Sikuliaq was moored 650m (0.4 miles) away. The vessel is a University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS) designated vessel and part of the US Academic Research Fleet (ARF), and is owned by the National Science Foundation and operated by the University of Alaska Fairbanks. It was equipped with an external global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver previously installed by Ethan Roth, the ship’s science operations manager and co-author of the study.

The team used data from the ship’s external GNSS receiver and open-source software to calculate changes in the vertical position of the R/V Sikuliaq down to the centimeter level. They created a time series showing the ship’s height before, during and after the landslide.

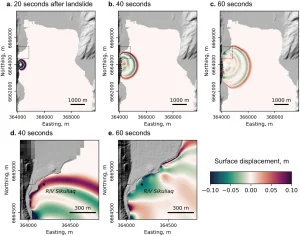

The researchers then compared the data to a landslide-tsunami model, which simulated the generation and movement of tsunami waves from the shoreline to the ship. Their results show that the ship’s vertical movement was consistent with the event, confirming the first detection of a landslide-generated tsunami from a ship’s satellite navigation system.

“I actually happened to be in Alaska at that time, retrieving seismometers from another study,” said CIRES fellow Anne Sheehan, a professor of geological sciences at CU Boulder and co-author of the study. “I decided to go visit the Sikuliaq, and it turned out that there had been a landslide that happened a day or two before. One of the crew members filmed it, and we were like, ‘wow,’ this is a great signal to try to find in the data.”

Research applications

Adam Manaster, then a graduate student working in Sheehan’s geophysics research group at CIRES and CU Boulder, took the lead on the project. In the report, the team points out that scientists currently rely heavily on earthquake-based observation systems to issue tsunami warnings, but these methods don’t always capture localized ground movement caused by landslides.

“This research proves that we can utilize ships to constrain the timing and extent of these landslide tsunami events,” Manaster said. “If we process the data fast enough, warnings can be sent out to those in the affected area so they can evacuate and get out of harm’s way.”

“Landslides into water can produce a tsunami, and some of them can be quite large and destructive,” said Sheehan. “Scientists have captured larger, earthquake-induced tsunamis using ship navigation systems. Our team had equipment in the right place at the right time to show this method also works for landslide-generated tsunamis.”

“The science shows that this approach works,” Sheehan said. “So many ships now have real-time GPS, but if we want to implement on a larger scale, we need to collaborate with the shipping industry to make the onboard data accessible to scientists.”

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation. The team also included scientists from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The work builds upon previous CIRES-led research, which demonstrated how GPS data from commercial shipping vessels could be used to improve tsunami early warning systems.

In related news, through a new analysis of satellite data, researchers at Penn State recently discovered that the side of the Anak Krakatau volcano was slipping for years and accelerated before the eruption and deadly ensuing tsunami in 2018. Click here to read the full story